On January 27, 2017, the Bundestag commemorated euthanasia victims in its annual commemoration of those who suffered and died under the Nazi dictatorship. The commemoration was dedicated to the sick and those in need of protection – according to the Nazi regime, such people were unworthy of life. They were the useless who ate food that might be used otherwise, parasites and vermin endangering the healthy folk, which meant they had to be eradicated. 300,000 people – including the mentally and physically disabled and the mentally ill – fell victim to the barbarity of the euthanasia program through systematic poisoning, gassing and starvation in mental hospitals and nursing homes right here in Germany. Instead of healing, caring for, and above all protecting their patients (!), the doctors and nursing staff in dozens of institutions viciously murdered them.

In a perverse, cynical manner, the organizers of the mass murder had provided themselves and the perpetrators of the mass murder with a false legitimation for their shameful actions: they convinced themselves that death was a redemption for the “soulless shells” of the sick. In this way, they twisted their betrayal of the oath to heal into a supposed beneficial and merciful act. Therefore, the sick murderers shielded themselves from feeling any remorse or compassion! The bulwarks of repression, denial and defense against guilt endured forever. After 1945, collective and individual memory vehemently resisted the burden of authentic memory. The majority of Germans wanted to forget and resented those who wanted to prevent them from doing so. The “traitors,” who strove to enlighten and come to terms with the past, were threatened with social exclusion far more so than the perpetrators who were able to leave their dark deeds in the past as desired.

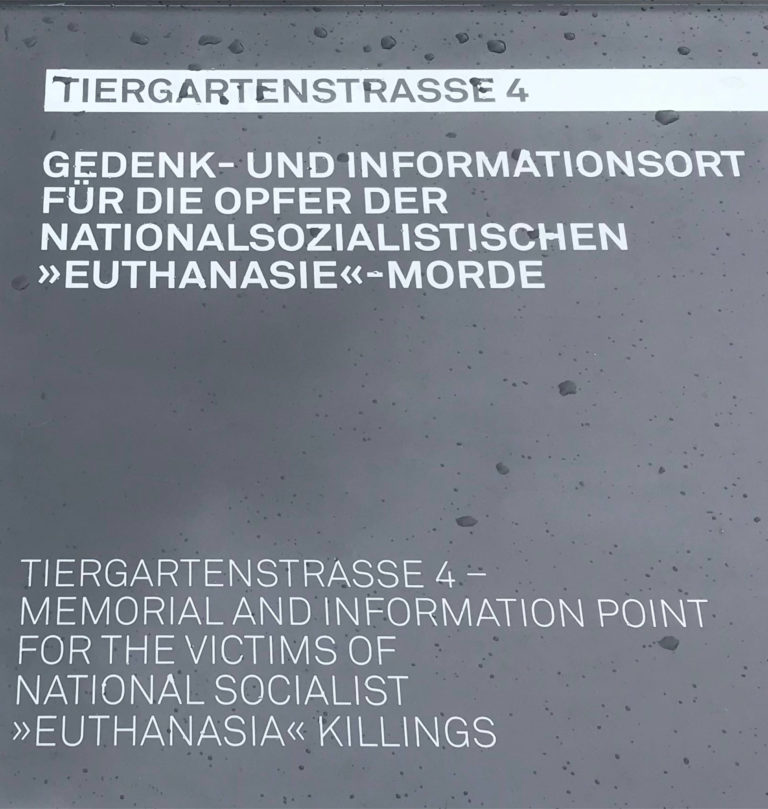

Thus, only a fraction of the medical staff involved in the mass murder of the sick ever had to stand trial. In many cases this happened only decades later and usually had no repercussions: the statute of limitations or a permanent inability to negotiate prevented a conviction. Meanwhile, the biographies of the perpetrators led to successful post-war careers, sometimes with rapid advancement. Who dared to stir things up here?! Therefore, it wasn’t until 2007 (!) that the German Bundestag found the courage to recognize the sick and disabled as victims of the Third Reich and to outlaw the Nazi law on forced sterilization. It was also only in 2011 that public funds were made available towards establishing a place of remembrance and information, which finally opened at Tiergartenstraße 4 – the seat of the former central office – in Berlin in 2014.

Psychiatry, too, has needed many decades to confront the chapter of its history that includes the crimes its professionals committed against humanity during the Nazi dictatorship. Its representatives and institutions were not prepared to do so until 2009. Like most other groups of perpetrators, the institution of psychiatry has chosen the time of self-confrontation with the topic of guilt and failure during the Third Reich in such a way that its confrontation has remained without any concrete perpetrators, i.e. perpetrators that could be brought to justice and punished under the law, simply because the passage of time had already placed these perpetrators outside the reach of earthly jurisdiction. Justice can only be experienced by survivors, if they still exist, and in their succession by family members through a symbolically conveyed form such as commemorative events, readings, memorials, etc.

It cannot be overlooked that this form of delayed confession of guilt is particularly beneficial for protecting the perpetrators, while their victims are constantly exposed to the demons of their memories.

Adequate lessons must be learned from this in the name of justice, i.e. the victims’ right to acknowledgment of their suffering and restitution.

Even if history – as is said – does not repeat itself, the history of disregard, torture and ill-treatment of the mentally ill in psychiatric institutions was by no means over when the Third Reich came to an end. To name but one particularly striking example of many of the post-war, post-reunification and recent past, the shocking documentary “The Hell of Ueckermünde” from the investigative journalist and chronicler of the Nazi reign of terror Ernst Klee, which captured the shocking conditions in an East German psychiatric ward in 1993, should be mentioned.

As the readers of my memoir “The Voices of Those Remaining” know, I myself am a survivor of a “treatment” administered by this institution; a treatment that had nothing curative about it at all, that was rather marked by violence, assaults, and complete disregard by the medical staff, and which left me deeply traumatized for years. In fact, this trauma took many years to overcome before I could reach the point where it was possible to talk about it in public.

The voices of most of my former companions have fallen silent: they are either no longer living or are barely able to participate in society.

In this context, I will also be speaking at the Leipzig Book Fair 2019 this year on behalf of the voices of those remaining that are not discernible in public space and for whom social participation is no longer possible, and demand that those who have been guilty in the past take responsibility for their actions: Here and now, not sometime and somewhere!

Dr. Christian Discher